CEO Insight: SDG 5- Closing the Gender Pay Gap

The legal community can play a crucial role in eradicating the pervasive gender pay gap, a nuanced issue that affects all women.

8 March saw the annual acknowledgement of International Women’s Day. A day where the global community celebrates women’s socio-economic and cultural achievements and recognises the ongoing struggle for equality that is still being fought by women around the world. This year’s theme ‘Embrace Equity’ identifies that indicators of gender equality, like access to education, health, politics, and the judicial system, vary for each woman, according to their circumstance. The global community must embrace inclusivity and bridge the gaps that make it so much harder for women of colour, working class women, women with disabilities, trans women, and all those experiencing marginalisation to succeed in an already unequal world.

Sustainable Development Goal 5 calls for universal Gender Equality by 2030. The Goal focuses on ending discrimination, exploitation, and violence against women, and ensuring women are offered opportunities and encouragement equal to men. The Goal also acknowledges the gender pay gap, with Target 5.5 focusing on the role of women in managerial and political positions as an indicator of women’s participation.

This month, I would like to explore the pervasive gender pay gap and the part each of us can play in reducing it. The gender pay gap is a nuanced issue that affects women in different ways due to the misunderstood nature of the ‘unexplained’ or ‘hidden’ gap. I hope that in bringing some light to the ways in which women are unfairly treated, the legal community will readily engage in the pursuit to eradicate the gender pay gap, as outlined in #SDG5 and #SDG8.

The Visible Gender Pay Gap

SDG 8.5 demands ‘equal pay for work of equal value’ by 2030. This aspect of the gender pay gap, where women are underpaid despite their labour market value being equal to that of men, is easy to observe through available data.

The European Commission, in its 2021 report, identified a gender pay gap of 12.7%, despite pay discrimination being enshrined in the European Treatise since 1957. Women would need to work 1.5 months extra a year in order to make up for this difference. Despite this, education statistics remain in women’s favour – 81% of young women reach secondary education compared to 75% of men, and women represent 60% of university graduates. However, post education, women make up only 8% of top companies’ CEOs.

A portion of the pay gap can be understood through the overrepresentation of women in low-paying sectors. Generally, classically feminised careers tend to be undervalued. For instance, women make up 80% of health and social work employees, an industry paid significantly less than other male dominated sectors, despite accounting for approximately 3.4% of global employment.

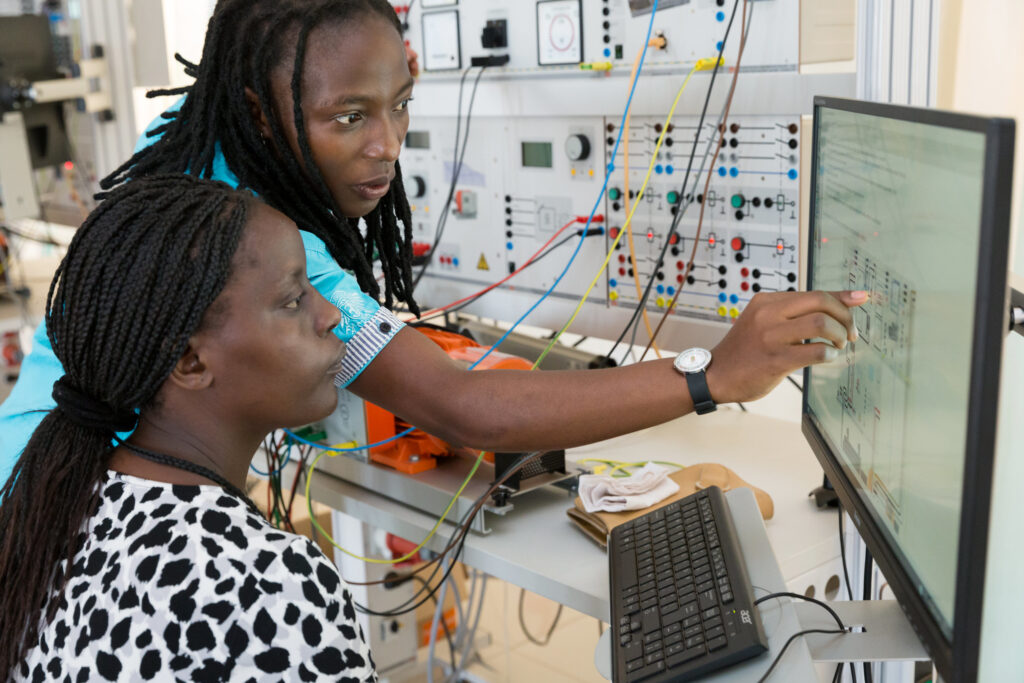

While women are slowly diversifying to less feminised careers, the pay gap remains; the legal sector, a highly male dominated industry, still sports a pay gap of 25.4% in the UK. Furthermore, the transition to different sectors isn’t fast enough to match global trends. The UN predict that by 2050, 75% of jobs will be related to STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics), while today, women hold just 22% of these positions. To understand why women still make up such a large part of low-paid industries, we must look at the driving forces behind these statistics.

The ‘Unexplained Pay Gap’

The ‘unexplained pay gap’ refers to imperceptible phenomena that affect the pay gap and are not easily understood through data. While women make up a large portion of university graduates and pay discrimination is illegal, women are still earning significantly less than men. To understand this difference, we must understand the cultural and societal expectations of women.

Globally, women are disproportionately assigned to be primary caregivers, spending on average 2.5 times as many hours on domestic work as men. This data varies significantly according to region – for example, in Pakistan this number is hugely inflated, with women undertaking 11 times the unpaid care and domestic work that men do. This generally means that women are taking significantly more career breaks in order to facilitate maternity and child care. Beyond this, women tend to hold part-time or flexible hours positions so they are able to prioritise child-care responsibilities.

The burden of unpaid family responsibilities falling to women forces them to take career breaks and obtain jobs that allow them to continue their child-care responsibilities alongside work. This phenomenon, referred to by Arlie Russel Hochschild as The Second Shift, is a cultural norm whereby women are expected to carry out hours of unpaid domestic labour, hindering their availability for paid work and career progression. In 2010 a Swedish study found that for every month of parental leave used by fathers, the mother’s wages increased by 7%, evidencing the benefits of shared familial burden. Additionally, the EU have found that differences in countries’ childcare provision policies correlate with the pay gap.

Furthermore, in STEM fields, where a growing number of women are graduating, even from the point of entry into their field women’s wages lag behind men’s of the same skillset, with the gap only widening over time. More research must be done into the challenges women face when trying to obtain jobs and advance in traditionally male dominated fields. For instance, when presented with a negotiable salary range, women are more likely to ask for the lower salary than men, perpetuating inequalities. If we again turn to Europe as an example, when accounting for career breaks and part-time work carried out by women, the lifetime gender-pay gap becomes 40%.

How Does this Effect Society?

The societal effects of women still being underpaid are numerous and the pay gap follows women into retirement. For example, women in United States retire with 30% smaller retirement pot than men. During their lives, women have generally poorer access to health care, welfare, and education, and are effected by the stress related effects of financial insecurity. During the Covid-19 pandemic, whilst women were generally at the forefront of the virus – dominating health care and public facing roles – fewer women were protected by government funded support such as income protection or furloughing schemes. This is because these schemes were not as readily available for domestic or part-time workers.

Furthermore, the unadjusted pay gap does not take into account bonus payments, seasonal payments, or commission. These are all things that are more difficult to attain when prioritising child-care responsibilities alongside work. It is clear that the gender pay gap needs to be considered in the greater context of gender inequality, rather than as a statistic. The societal benefits of addressing the gender pay gap are extreme, with the OECD predicting that by closing the gender pay gap, women’s earnings could increase by $2 trillion – money that would be circulated back into the economy.

Lower salaries and less stable incomes deter women from owning property or being active economic contributors. In some countries women are completely excluded from financial independence. For example, women in developing nations are 6% less likely than men to have a bank account. Also, there are still 72 countries globally where women are not allowed to open a bank account. Further, women-owned businesses in developing nations find it difficult to obtain credit or business loans due to their lack of financial collateral such as ownership of land or other financial resources. The World Economic Forum findings indicate that 80% of women-owned businesses have credit needs that are unserved or underserved. These global inequalities underscore the importance of equity in the pursuit of pay parity.

Solutions

The International Labour Organization found that economies increasing gender participation results in significant economic growth. The current underrepresentation of women in high paying roles excludes them from decision making, land ownership, and creates a cycle wherein women are prevented from reaching their potential. In order to meet the 2030 global agenda for Sustainable Development, gender parity in the workplace is essential.

The World Economic Forum has estimated it will take 151 years to close the gender pay gap if current trends are to continue. However, taking into account the ‘unexplained gap’, gender parity could be reached sooner if actions are taken now. In December 2022, the European Parliament agreed on a directive to make salaries more transparent, giving employees the right to access ‘sex-disaggregated’ data if the organisation employs over 100 people. Lawyers can play an essential role in ensuring transparency in organisations, helping to put this directive into practice across the EU and supporting female workers when they are proven to be underpaid.

Furthermore, in 2021 the European Commission produced a proposal for gender parity that included a work-life balance directive, ensuring companies made it easier for both parents to attend to family responsibilities; a European care strategy to support this; and a directive ensuring 40% of board-members should make up the company’s underrepresented sex.

Studies have shown than when an organisation has more female managers, the pay gap tends to be smaller. As reasoned above, women are often held back from progressing into managerial roles contributing to an underrepresentation of women in leadership; companies should make it a priority to support women into these positions, in order to perpetuate equal pay.

Governments must invest in childcare policies, allowing women to focus on their careers without the burden of unpaid care work. Likewise, companies should allow for men to take parental leave and offer flexibility of working for both genders, in order for families to share childcare responsibilities more easily.

As a business or organisation there are practical steps Law Firms can take:

- Promote a gender inclusive business culture

- Implement transparent pay structures and reviews

- Base pay on the position itself rather than on the employee’s previous pay

- Provide a more flexible working culture enabling women to access higher-level jobs

- Share results with other organisations such as EPIC

Law Firms and General Counsel have a crucial role to play in enabling these solutions. When advising clients, they can ensure that their clients are adopting these policies that encourage equitable gender pay. By suggesting and drafting clauses within contracts, legal professionals can ensure that organisations are becoming gender equitable workplaces. There is also an opportunity to work with governments to draft legislation and policy that encourage organisations to adopt gender equitable business practices. Joining A4ID’s Pro Bono Brokerage gives legal professionals an opportunity to get involved in such valuable projects.